Asthma Treatment & Control in London

Asthma control is a measure of the reduction in symptoms, prevention of exacerbation, and maintenance of good lung function. Current guidelines state that well controlled asthma requires no symptoms, no exacerbation, and normal lung function.

A friendly team of allergy, immunology and respiratory medicine consultants as well as ENT surgeons will do our best to look after patients with allergic and non-allergic asthma as in a multi-disciplinary approach.

People with aspirin sensitivity NSAID-Exacerbated Respiratory Disease (NERD) can develop symptoms of several conditions lined to Aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease (AERD), also known as Samter’s Triad.

The condition is named after an immunologist, Max Samter, who first identified it, while ‘Triad’ refers to the three key components involved. Asthma, aspirin and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) sensitivity, and nasal polyps make a complex chronic medical condition that requires several specialities to be involved.

We do assessment for biological treatment (monoclonal antibodies) of patients with severe asthma and nasal polyps.

Health professionals should tailor asthma review to allow for patient preference (including frequency of professional review), as well as asthma severity, risk of severe attacks, and the type of maintenance treatment plan in place.

More information about asthma and proper asthma management is available on the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) website www.ginasthma.org

The Asthma Control Test is available free of charge at www.asthmacontroltest.com

Peak Flow Diary

This great site helps you (and your doctor) to monitor your asthma

http://peak-flow-diary.co.uk/index.php

Step 1 – Record

The first step is to record your peak flow reading, using the form shown below. The form is simple just time, date and reading.

Step 2 – View Chart

Your peak flow readings are then plotted on the graph.

Peak Flow Meter

Peak Flow Predicted values for Adults View Chart

You will need to match your age and height on the chart.

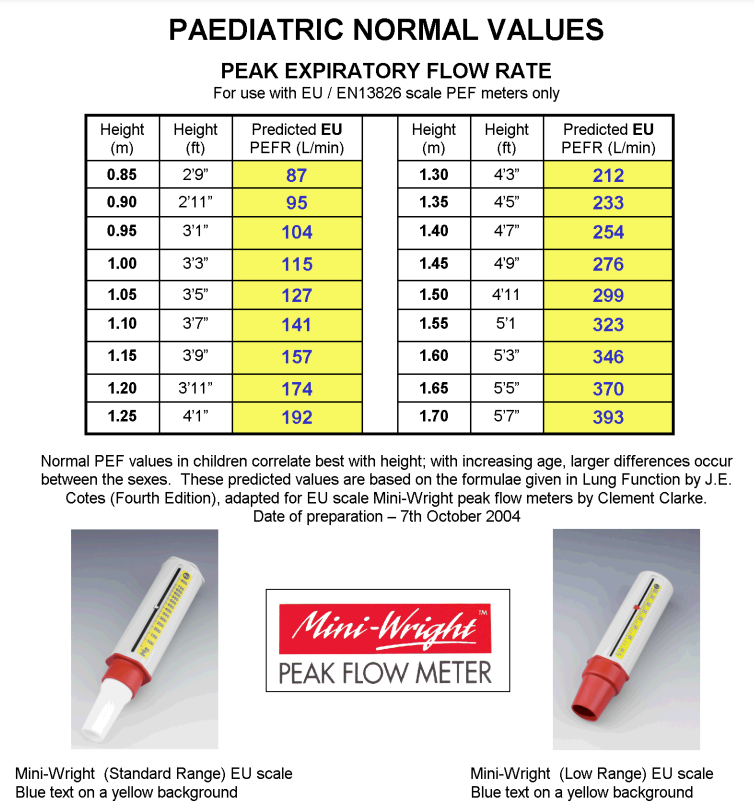

Peak Flow Predicted values for children

Is the new EU-scale meter the same as the ATS-scale meter?

No. Whilst the scale may look similar, only meters that display the text ‘EN 13826‘ have been tested to the new standard. The EN13826 standard includes two important ‘airflow waveforms’ that are not part of the ATS test procedure for peak flow meters. Some ATS-scale meters have already been shown as failing the new EN 13826 standard .

Asthma severity is based on clinical features, as defined in the following table:

| Classification | Day-time symptoms | Night-time symptoms | PEFR* | PEFR variability** |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intermittent | 1 time per week or less | Twice per month or less | =/>80% | <20% |

| Mild persistent | 1 time per week or more but less than once per day | Twice per month or more | =/>80% | =20-30% |

| Moderate persistent | Daily | Once a week or more | =60-80% | 30% |

| Severe persistent | Daily | Frequent | =/<60% | 30% |

| *PEFR = peak expiratory flow rate as a percentage of expected PEFR according to patient age and height **PEFR variability = the difference between morning and evening flow rates |

||||

Check your spirometry predicted values, record peak flow results in our chart

The Global Asthma Report 2011 http://www.globalasthmareport.org

Asthma affects 235 million people today and prevalence is rising. Low- and middle-income countries suffer the most severe cases.

We have the tools to counter the devastating personal and economic impact of untreated and poorly managed asthma.

The British Asthma Guideline recommends the Royal College of Physicians three questions to assess asthma control over the preceding month.

Have you had any difficulty sleeping because of asthma symptoms, have you had your usual asthma symptoms during the day, and has your asthma interfered with your usual activities?

A personal asthma action plan is a tailored written record of what action to take when symptoms or peak flow readings deteriorate. It includes information about when the patient needs to seek medical help or emergency care. This encourages the patient to take more responsibility for their asthma management.3 Patients should be given autonomy to step up and step down their treatment as detailed in their asthma action plan, in response to their symptoms or peak flow monitoring.

Additional resources

Asthma UK

http://www.asthma.org.uk/index.html

BTS SIGN Guidelines

http://www.sign.ac.uk/guidelines/fulltext/101/index.html

GINA

Asthma review and action plan guidelines

http://www.pcrs-uk.org/resources/asthma_guidelines.php

- National Asthma Panel. Data from Health Survey for England 2001, Joint Health Surveys Unit, 2003, The Scottish Health Survey 1998, Joint Health Surveys Unit, 2000, Census 2001 (Office for National Statistics). Asthma UK 2006.

- Powell H, Gibson PG. Options for self management education for adults with asthma. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2002, Issue 3. Art No: CD004107.

- McArthur R, Stephenson P (Eds). Personal Asthma Action Plans. 2008: GPIAG Opinion No 12.

- Pearson MG, Bucknall CE, editors. Measuring clinical outcome in asthma: a patient-focused approach. London: Royal College of Physicians; 1999

- Pinnock H, Levy M (Eds). Asthma Review 2008: GPIAG Opinion No 23.

- Pinnock H, Fletcher M, Holmes S, et al. Setting the Standard for routine asthma consultations: a discussion of the aims, process and outcomes of reviewing people with asthma in primary care. Primary Care Respiratory Journal 2010;19(1):75-83.

Biomarkers in Asthma

Biomarkers play a pivotal role in guiding the management of asthma by predicting treatment responses in clinical practice.

Three principal biomarkers—peripheral blood eosinophil count, serum free immunoglobulin E (IgE) concentration, and fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO, sometimes referred to as T2 biomarkers)—are employed to assess airway inflammation and patient subtypes.

Blood eosinophils and FeNO levels are frequently correlated, whereas the measurement of serum free IgE can indicate a distinct immunological profile, particularly in those cases where only IgE levels are raised.

Patients demonstrating concurrent elevations in all three markers experience significantly worsened clinical outcomes, reflected by increased exacerbation rates, suboptimal sputum eosinophil clearance, and reduced pulmonary function.

Clinical evidence underscores that individuals with persistent blood eosinophilia (with counts exceeding 300 cells/µL) remain at elevated risk for asthma exacerbations, increased emergency department presentations, hospital admissions, and high-dose systemic corticosteroid use, even when classical symptoms appear well-controlled.

Ongoing eosinophilic activation, corroborated by both sputum and blood biomarker assays, persists despite adherence to maintenance therapies including inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), long-acting β2-agonists (LABA), and leukotriene modifiers.

These findings necessitate regular monitoring of inflammatory markers and underscore the inadequacy of symptom-based assessments alone in severe cases.

Severe asthma is distinguished by a heightened baseline eosinophil burden, progressive decline in forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1), and increased secretion of eosinophil-derived proteins such as eosinophil-derived neurotoxin (EDN).

Notably, the formation of eosinophil extracellular traps (EETs) is observed more frequently in severe asthma, contributing to irreversible airway tissue damage and more pronounced declines in lung function.

Comorbidities including chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) with T2-high endotype, as well as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID)-exacerbated respiratory disease (NERD, also known as NELD in transcript), are significantly associated with adverse outcomes and necessitate precise, phenotype-driven therapeutic strategies.

Biological therapy selection should be dictated by the presence and severity of comorbidities. For example, patients exhibiting severe CRS with nasal polyps may derive optimal benefit from epithelial cell-targeted biologics, whereas those with comorbid urticaria are more appropriately managed with biologics targeting mast cells, such as omalizumab.

A repertoire of six T2-directed biologics is available, and real-world studies have demonstrated favourable response rates to agents including mepolizumab.

Nevertheless, careful post-marketing surveillance and real-world evidence are crucial to delineate non-responder populations and inform therapeutic decisions.

Switching or combinational use of biologics—such as dual administration of anti-interleukin-5 and dupilumab—may be considered in partial response or therapy-induced eosinophilia.

Additionally, fungal sensitisation, particularly due to Aspergillus fumigatus, is prevalent in patients with severe eosinophilic asthma, necessitating routine assessment in this cohort.

Special clinical challenges are encountered in elderly individuals who often exhibit a T2-low inflammatory phenotype and possess an attenuated response to standard asthma therapies.

Metabolic comorbidities, such as hyperlipidaemia and overweight status, are especially relevant in older and female patients, resulting in further diminution of disease control.

Moreover, primary immunodeficiencies, notably involving immunoglobulin G (IgG) subclass deficiencies, warrant evaluation in poorly controlled cases and may require adjunctive immunoglobulin replacement therapy.

Unmet medical needs persist in the management of T2-low, neutrophilic, and mixed granulocytic asthma, and there is an imperative for research into improved biomarkers and novel treatments for neutrophilic airway inflammation and autoimmune contributions to asthma pathology.

Of particular note are mixed eosinophil-neutrophil phenotypes and persistent mucus plugging of the airways, which pose substantial management difficulties and may necessitate adjunctive therapy with macrolide antibiotics or combinatorial pharmacological strategies.

These findings support an intensive, individualised approach to asthma management, incorporating comprehensive biomarker panels, systematic comorbidity screening, and precision therapeutic selection.

- References:

Bel EH, Wenzel SE, Thompson PJ, et al. Oral glucocorticoid-sparing effect of mepolizumab in eosinophilic asthma. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(13):1189-1197. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1403291

Ekman M, Bjerg A, Tunsäter A, Lindmark B, Nwaru BI, Lundbäck B. Fungal sensitization and its relationship with asthma. Clin Transl Allergy. 2017;7:29. doi:10.1186/s13601-017-0162-5

Bachert C, Han JK, Desrosiers M, et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab in patients with severe chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps (SINUS-24 and SINUS-52): results from two multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group phase 3 trials. Lancet. 2019;394(10209):1638-1650. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31881-1

Pavord ID, Beasley R, Agusti A, et al. After asthma: redefining airways diseases. Lancet. 2018;391(10118):350-400. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30879-6